In 1936, when Chatsworth Court was completed, you can just imagine Agatha Christie’s Hercule Poirot admiring the ‘fine flats in an exceptionally distinguished area’. Still highly sought after today, Chatsworth Court may not have been home to Poirot, but they were home to the children of explorer Sir Ernest Shackleton, including geographer and politician, Edward, Baron Shackleton, along with world-famous actress and star of Dynasty, Joan Collins.

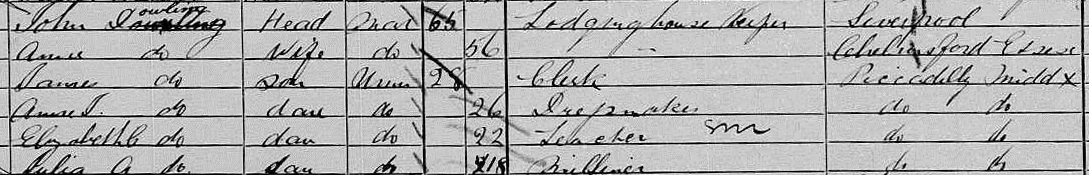

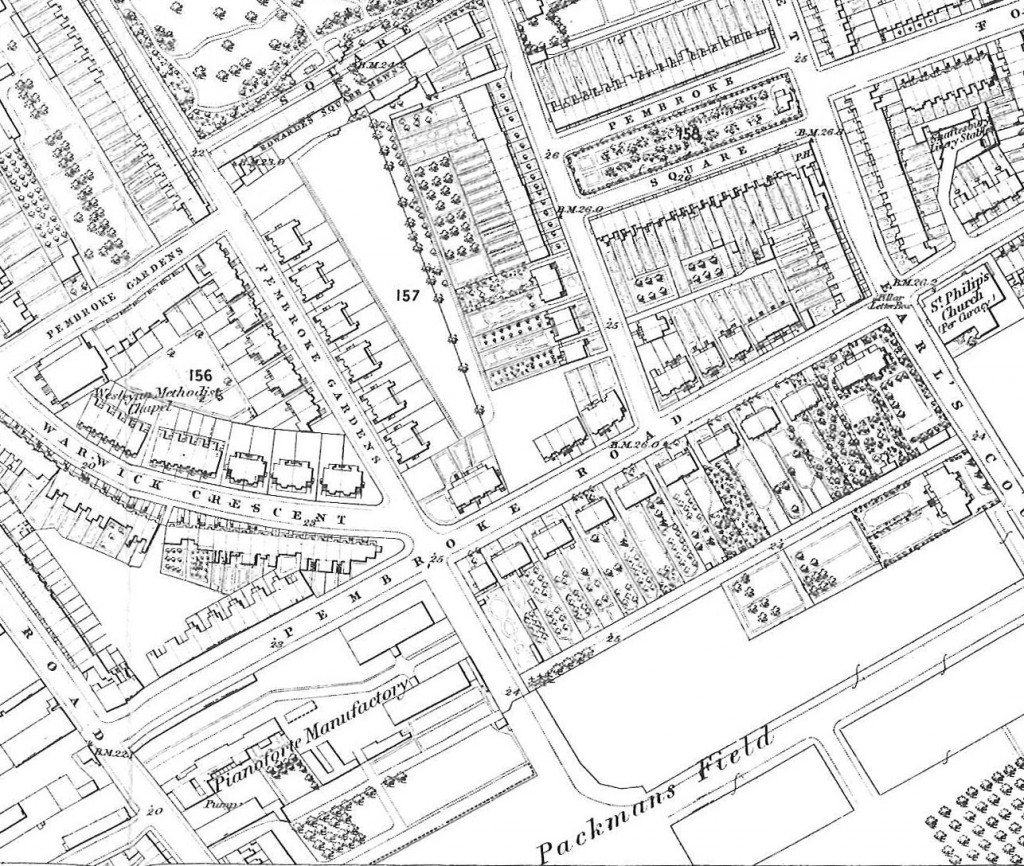

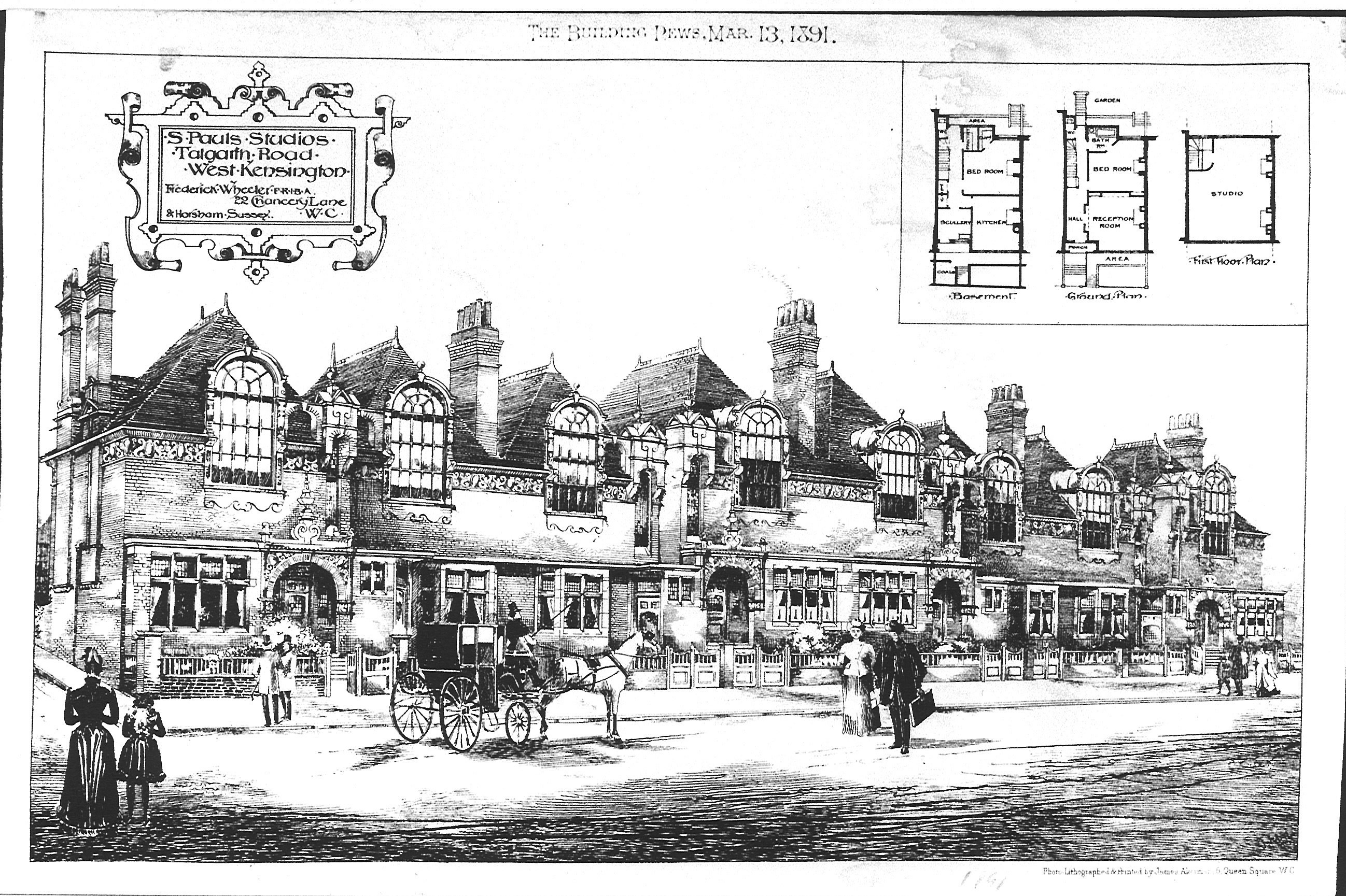

Prior to the building of Chatsworth Court, this part of Pembroke Road was covered by a row of paired villas, built in the 1840s by local builder, Stephen Bird. Pembroke Road was named for the connection with former landowners, the Edwardes family, and their estate in Pembrokeshire in Wales. The street was laid out over farmland in the 1820s, but the houses were only completed later during the 1840s.

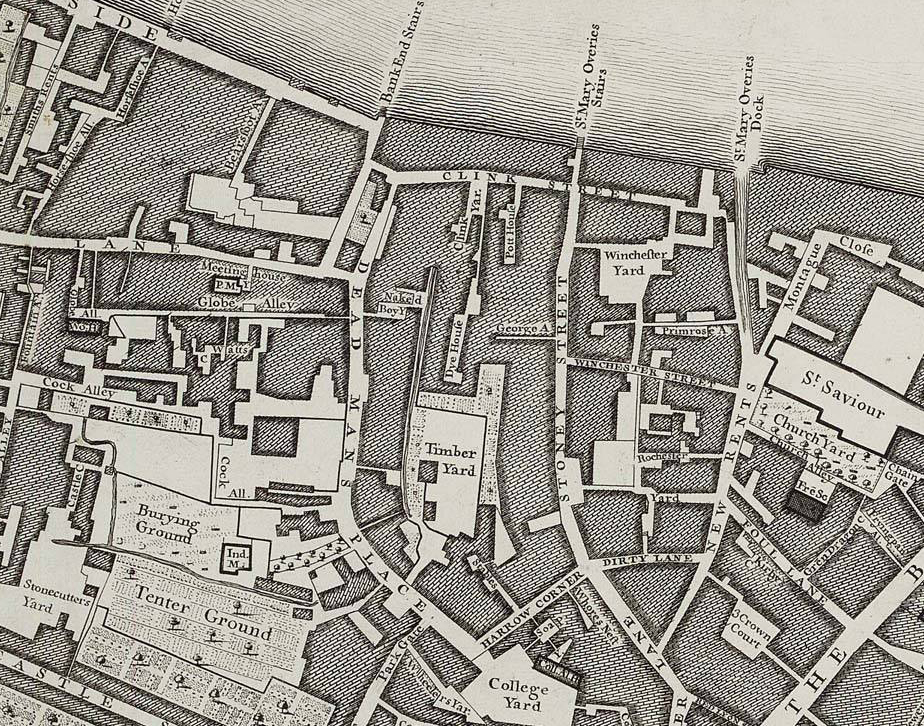

The Ordnance Survey map also reveals that to the west, past the paired villas, was a ‘Pianoforte Manufactory’. This was the former factory of celebrated French piano and harp manufacturers, Messrs Erard. It was built in the early 1850s and by 1855 the factory was producing over 1,000 pianos and harps with around 300 workers. However, by 1891 the factory had closed and the site was taken for residential flats, Warwick Mansions, along with warehouses (also later replaced with flats).

The new century also brought change to the eastern end of Pembroke Road, with the demolition of the Victorian villas and the building of two new blocks of flats – Chatsworth Court and Marlborough Court. On the corner of Earl’s Court Road was the larger Chatsworth Court, designed by H.F. Murrell and R.M. Pigott and completed in 1935. Murrell and Piggott were responsible for several other blocks in London, including neighbouring Marlborough Court and Ovington Court in Knightsbridge.

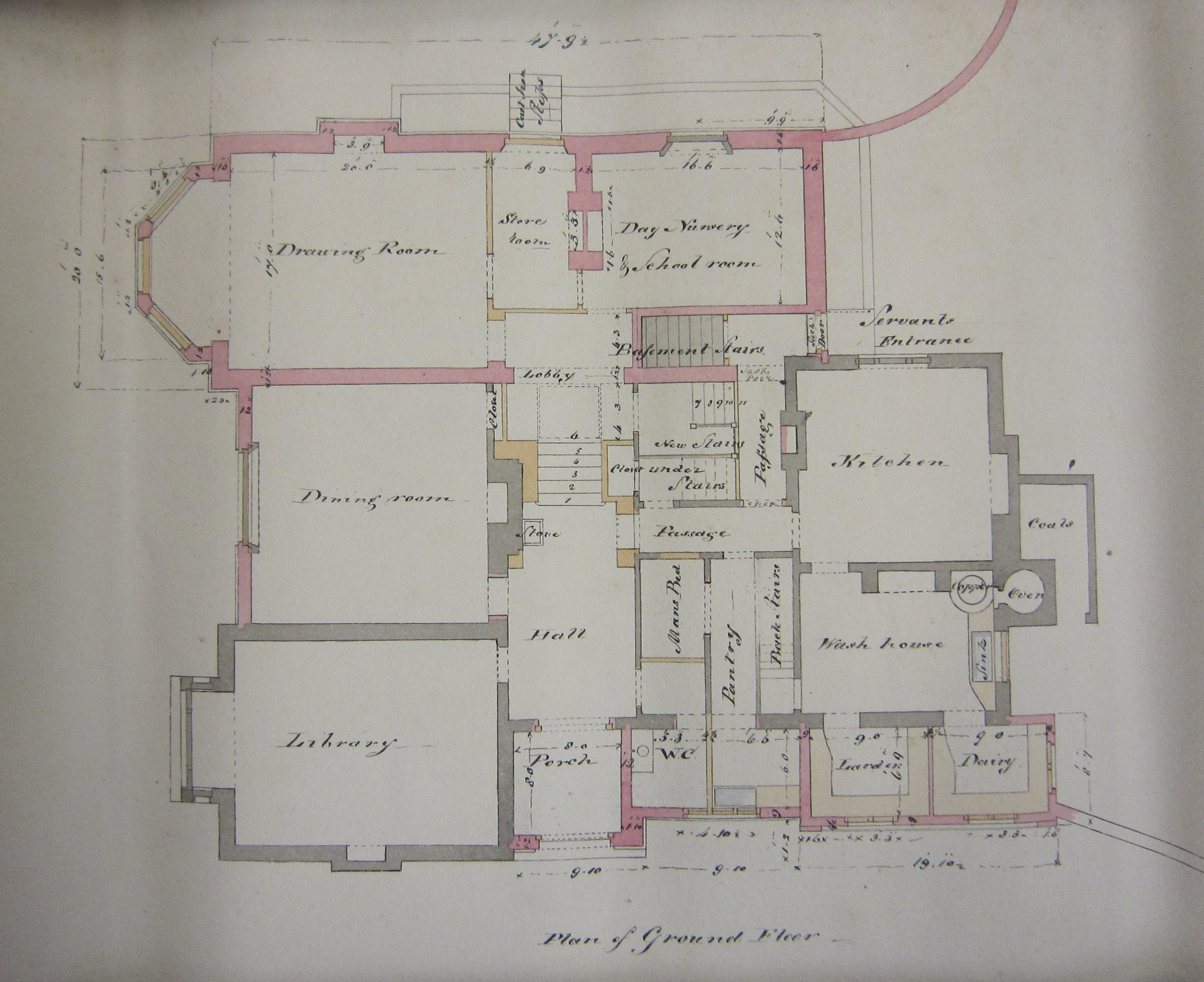

The new flats were promoted as ‘a country club in a garden’ with modern fitted kitchens and bathrooms (a key selling point in a day when this was not necessarily the norm) and a range of luxury facilities, including tennis and squash courts, swimming pool, restaurant, internal telephones, optional maid services, electric clocks and heated towel rails. The brochure promoted the flats ‘near the centre of things, but surrounded by trees [where] one can live well but unostentatiously: quietly but socially’. When first advertised in 1936 there were six different types of flats ranging from £130-£350 p.a. inclusive.

The first residents began to move in during late 1936 and 1937 and by 1938 occupants included Lady Ellen Palmer and Lady Raeburn, along with Lieutenant-Colonel Gaskell and Colonel Langstaff.

However, one of the most noted early families to move into Chatsworth Court were the children of Antarctic explorer, Sir Ernest Shackleton. At flat No.38 in 1938 was his eldest son, Raymond Shackleton, while at flat No.118 was Raymond’s sister, Cecily. Sir Ernest Shackleton’s youngest son, Edward, later Baron Shackleton, was also recorded living in Chatsworth Court with his wife Betty in 1940.

In 1934 Edward Shackleton organised and took part in the Oxford University expedition to Ellesmere Island and during the Second World War served as Wing Commander in the RAF. He was appointed O.B.E. in 1945 and from 1946 to 1955 he served as a Labour MP. He was created Baron Shackleton in 1955 and later went on to serve as Minister of Defence for the RAF, Leader of the House of Lords, and also President of the Royal Geographical Society.

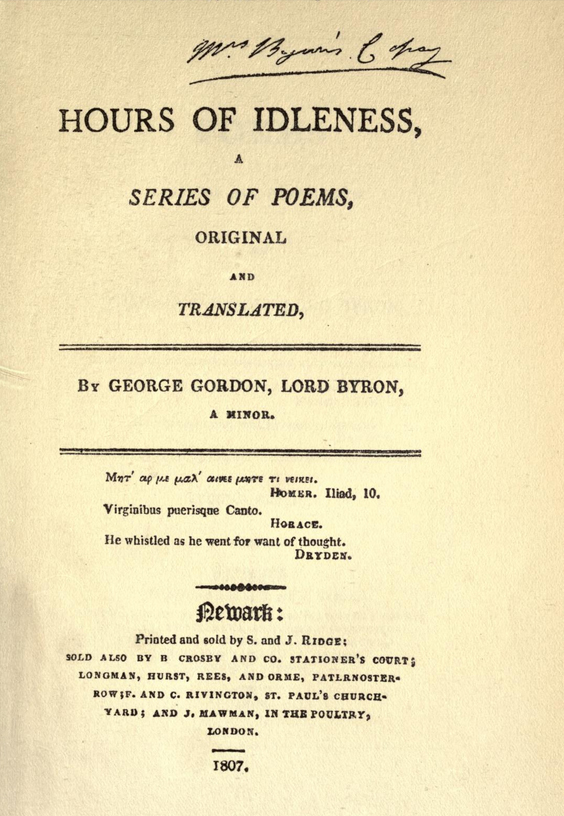

Other notable residents of Chatsworth Court have included screenwriter, H. Fowler Mear, who wrote many screenplays, including Lord Edgeware Dies (1934) and Scrooge (1935). It was also home to Nixon Hilton of Nixa Records, later Pye Nixa, who distributed records for Petula Clark, The Searchers and The Kinks.

However, one of the most famous former occupants was actress and author, Dame

Joan Collins, who lived at Chatsworth Court during the 1960s with her second husband, actor and songwriter, Anthony Newley.

The Circus, first known as The King’s Circus, was designed by John Wood the Elder in the 1740s with the foundations laid in 1754. However, John Wood the Elder died just three months later and it was left to be completed by his son, John Wood the Younger. It features three sections, completed over a period of years, and the final section completed and occupied in 1768. The Circus is impressive when viewed as a whole, but it is also in the detail that it features ‘…a tour-de-force of external decoration’. Each level features paired columns of the different classical order – Doric on the ground, Ionic on the first, and Corinthian on the third. Amongst the many decorative details it also includes a carved frieze with hundreds of pictorial symbols, including emblems of science, arts, and industry.

The Circus, first known as The King’s Circus, was designed by John Wood the Elder in the 1740s with the foundations laid in 1754. However, John Wood the Elder died just three months later and it was left to be completed by his son, John Wood the Younger. It features three sections, completed over a period of years, and the final section completed and occupied in 1768. The Circus is impressive when viewed as a whole, but it is also in the detail that it features ‘…a tour-de-force of external decoration’. Each level features paired columns of the different classical order – Doric on the ground, Ionic on the first, and Corinthian on the third. Amongst the many decorative details it also includes a carved frieze with hundreds of pictorial symbols, including emblems of science, arts, and industry.