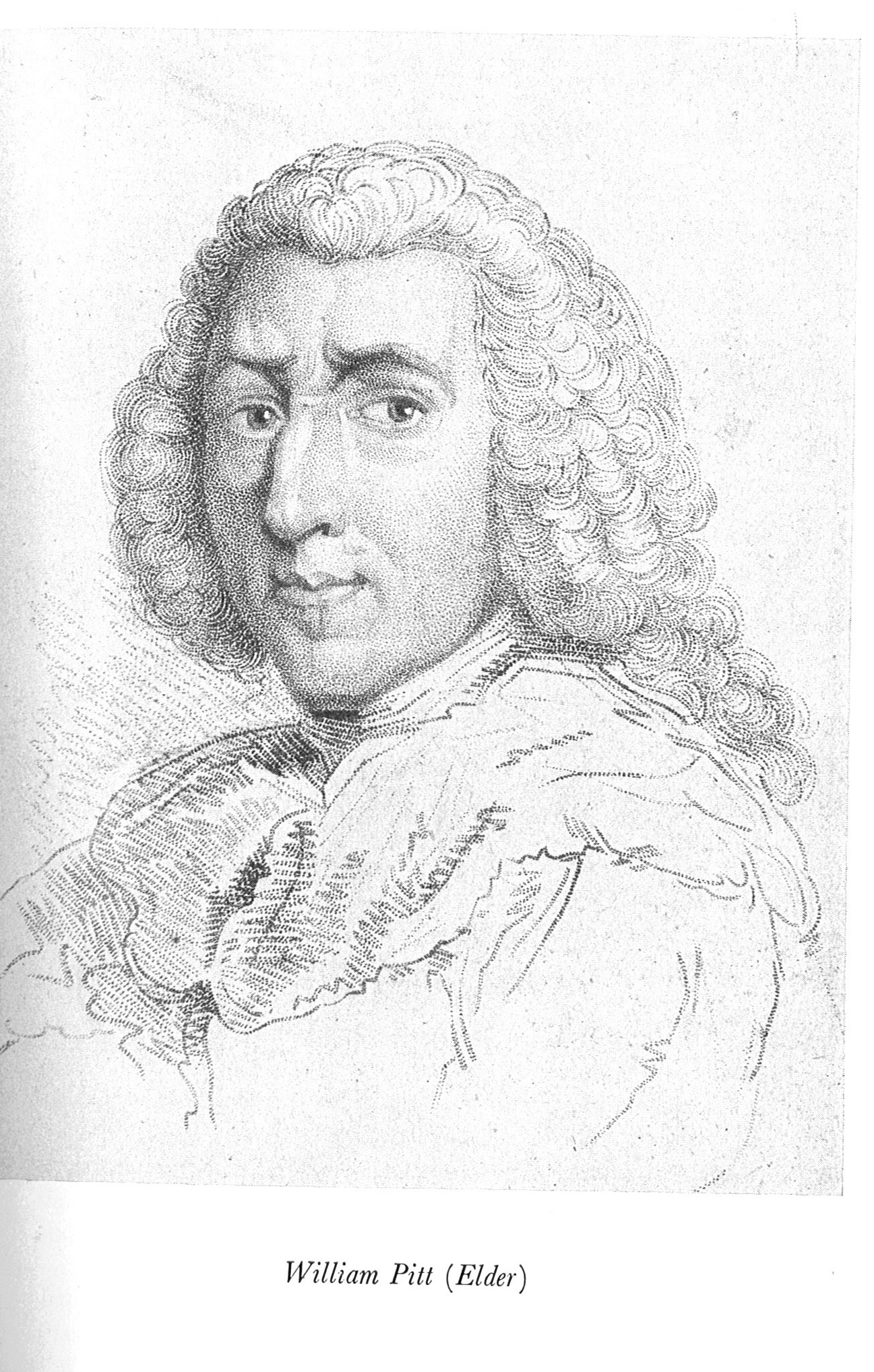

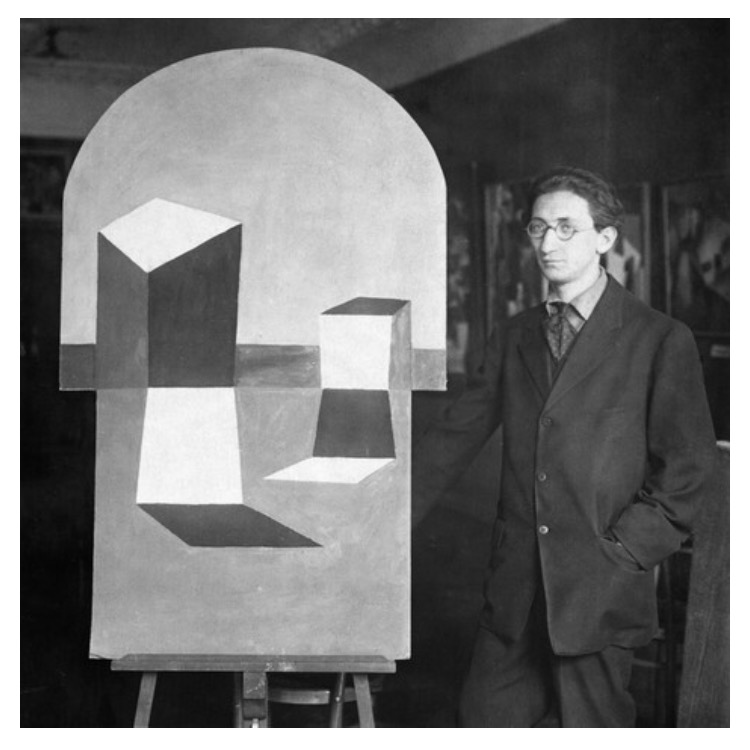

UPDATE: Since writing the post on the artist Peter Laszlo Peri and his former home in Willow Road, Hampstead, I have been contacted by Peter Peri’s grandson, also an artist and also named Peter Peri like his grandfather. I was delighted to receive feedback from the Peri family and their admiration of my blog post. But, alongside this, Peter Peri (the younger) was kind enough to offer some samples of his grandfather’s Constructivism artworks, including this one of the man himself in Berlin in c.1921! There is also a new website devoted to Peter Laszlo Peri, with further details about his life and work – go to www.peterlaszloperi.org.uk

As mentioned in my earlier post below, some of Peter Laszlo Peri’ post-war sculptures have recently been listed by Historic England and feature in the recent focus on post-war public art. However, some of Peter Laszlo Peri’s earlier works may not be so widely recognised. You can view more of Peter Peri’s Constructivism works on Pinterest here – http://uk.pinterest.com/emmanuelleperi/laszlo-peter-peri/

So, next time you’re wandering around Hampstead or heading to Hampstead Heath on the weekend, you can think of the lesser-known Hungarian artist, Peter Lazslo Peri, a few doors away from the more famous Goldfinger.

Happy new year! As it has been a month since my last blog post, I haven’t had the chance to wish everyone a happy new year :-) I have been a little distracted by having a holiday, but also working on the proposal for my next book, as well as further research into an 18th century house in the Cotswolds. However, it is now time for another blog post!

Willow Road in Hampstead is most known for the Grade II* listed home of Hungarian architect, Ernö Goldfinger, who was made famous by Ian Fleming in the James Bond book, Goldfinger, in 1959. The real Goldfinger built his home at Nos.1-3 Willow Road in 1937-9 and it was much criticised when first completed. However, today, it is praised as a ‘Unique and influential modernist home’. No.2 Willow Road is now in the hands of The National Trust and can be visited at set times – No.2 Willow Road.

Willow Road in Hampstead was formerly a track way running adjacent to the Fleet River and was officially named Willow Road in 1845, which is believed to have been inspired by Willow trees planted at that time. It was developed with houses later in the 19th century, which included No.10 (originally No.3) constructed during the early 1880s. The first resident to move in was a school master, Mr. William Adams.

William Adams and his wife, Mary, also a school mistress, lived at the house in Willow Road through to the early 1900s. During this time, William and Mary rented out rooms in the house, which in 1891 included a fellow school mistress, Ellen Whelan, and in 1901 two brothers who were both clerks for the East India Company. Also in 1901 they had a visitor in the house, a singer, 27 year old Elizabeth Davies.

After the first world war, No.10 Willow Road became the home of a writer and essayist, Wilkinson Sherren, most remembered today for his Thomas Hardy guide to Wessex, The Wessex of Romance, published in 1902.

However, it was late in the 1930s, as war was about to break out again that the house became the home of Hungarian artist and sculptor, Peter Laszlo Peri. Born Ladislas Weisz in Hungary, he changed his name to Laszlo Peri when he moved to Germany in the 1920s, and then again, to Peter Peri, when he moved to England.

Peter Peri appears to have been a man of many talents, having previously been a bricklayer, as well as studying drama and architecture, before becoming an artist after moving to Berlin in the 1920s. He became a leading artist in the style of Constructivism, but it was also while in Germany that he became actively involved in politics with strong links to socialism and communism. Peri left Germany with his wife in 1933, the same year Adolf Hitler became Chancellor.

Peri moved from paintings to sculpture in the late 1920s, but in particular it was after his move to England that he soon gained a name for his work in figurative sculpture.

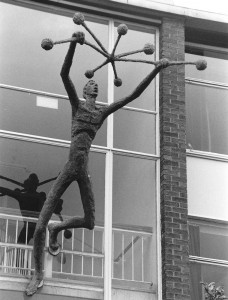

Peter Peri and his wife Mary continued at No.10 Willow Road throughout the years of the Second World War, and after the war Peter continued his work in sculpture, particularly with concrete. He was also noted for his ‘horizontal reliefs’ which featured on the sides of buildings or strategically placed to accompany architectural features. After the war, he had several solo exhibitions, as well as working on many private and municipal commissions. These included a solo exhibition at AIA Gallery in London in 1948, as well as the Whitechapel Gallery in 1953 and the Tate Gallery in 1958.

Peri completed a number of sculptures for schools, including several in Leicestershire and Warwickshire, but also completed projects for London County Council, and also the Ministry of Information. However, he is often most remembered for his sculpture, Sunbathers, for the Festival of Britain at Southbank in 1951. The sculpture is remembered for its aesthetic quality, but it is also remembered today because it is listed amongst the post-war sculptures that have gone missing!

Historic England is currently promoting a call to ‘Help Find Our Missing Art’, with a long list of public works of art that have either been destroyed or gone missing. Recognising that most of the art may never be seen again, they are putting out a call for photographs, stories, and memories of the art from members of the public. If you’re interested you can follow the link highlighted above for more details. Historic England will also hold an exhibition at Somerset House, Out There: Our Post-War Public Art that will ‘follow the fates and fortunes’ of post-war public art, from February to April 2016.

Peter Laszlo Peri continued to exhibit his works and complete sculpture commissions throughout the 1950s and 60s, until he died in January 1967. Today, his works are held by a number of galleries across the country, including The Tate Gallery, The British Museum, Leeds City Art Collections, as well as the Hungarian National Gallery and The Arts Council.

Peter Peri may not have been made famous by being named as an evil character in a James Bond novel, but he certainly left an artistic legacy across Britain during the post-war period and is remembered as the other Hungarian of Willow Road, Hampstead.

![1_2_3_Willow_Road_Hampstead_London_20050924[1]](http://www.house-historian.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/1_2_3_Willow_Road_Hampstead_London_200509241-1024x768.jpg)

The Circus, first known as The King’s Circus, was designed by John Wood the Elder in the 1740s with the foundations laid in 1754. However, John Wood the Elder died just three months later and it was left to be completed by his son, John Wood the Younger. It features three sections, completed over a period of years, and the final section completed and occupied in 1768. The Circus is impressive when viewed as a whole, but it is also in the detail that it features ‘…a tour-de-force of external decoration’. Each level features paired columns of the different classical order – Doric on the ground, Ionic on the first, and Corinthian on the third. Amongst the many decorative details it also includes a carved frieze with hundreds of pictorial symbols, including emblems of science, arts, and industry.

The Circus, first known as The King’s Circus, was designed by John Wood the Elder in the 1740s with the foundations laid in 1754. However, John Wood the Elder died just three months later and it was left to be completed by his son, John Wood the Younger. It features three sections, completed over a period of years, and the final section completed and occupied in 1768. The Circus is impressive when viewed as a whole, but it is also in the detail that it features ‘…a tour-de-force of external decoration’. Each level features paired columns of the different classical order – Doric on the ground, Ionic on the first, and Corinthian on the third. Amongst the many decorative details it also includes a carved frieze with hundreds of pictorial symbols, including emblems of science, arts, and industry.