A short time ago I was asked to research the history of this striking 17th century house in Lincolnshire. Despite being tucked away in a quiet village in rural Lincolnshire, this house has a number of connections to prominent historic figures and events, including two wives of King Henry VIII and the Putney Debates during the Civil War.

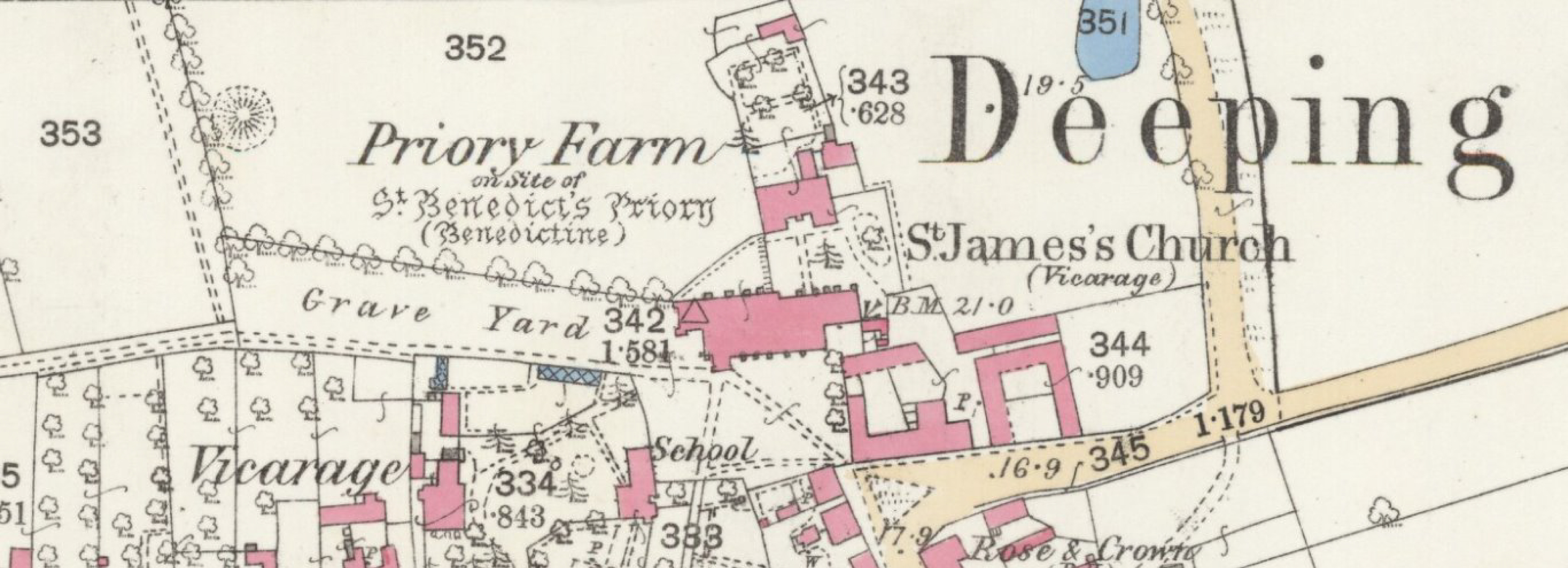

The house is situated on the historic site of the former 12th century Benedictine priory, established in 1139, as part of Thorney Abbey in Cambridgeshire. However, in 1539, it suffered the same fate as the Abbey and was reclaimed under Henry VIII’s Dissolution of the Monasteries. In 1540, the lands and buildings were given to Tudor politician, Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk, who was also the uncle of two of Henry VIII’s wives, Anne Boleyn and Catherine Howard.

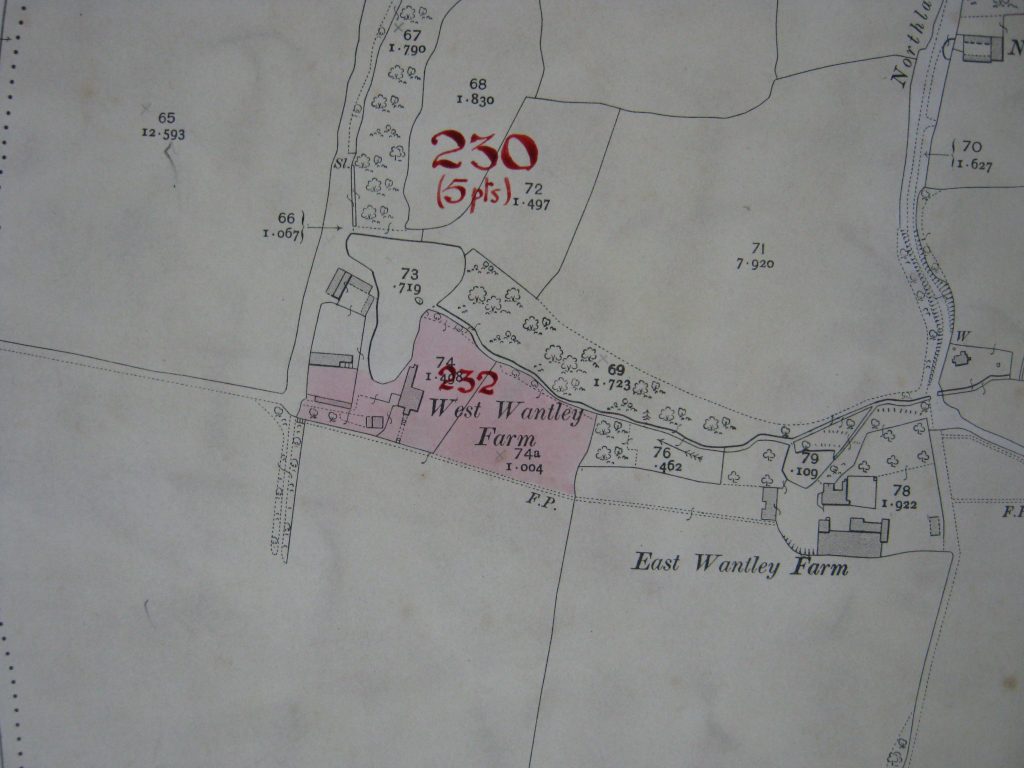

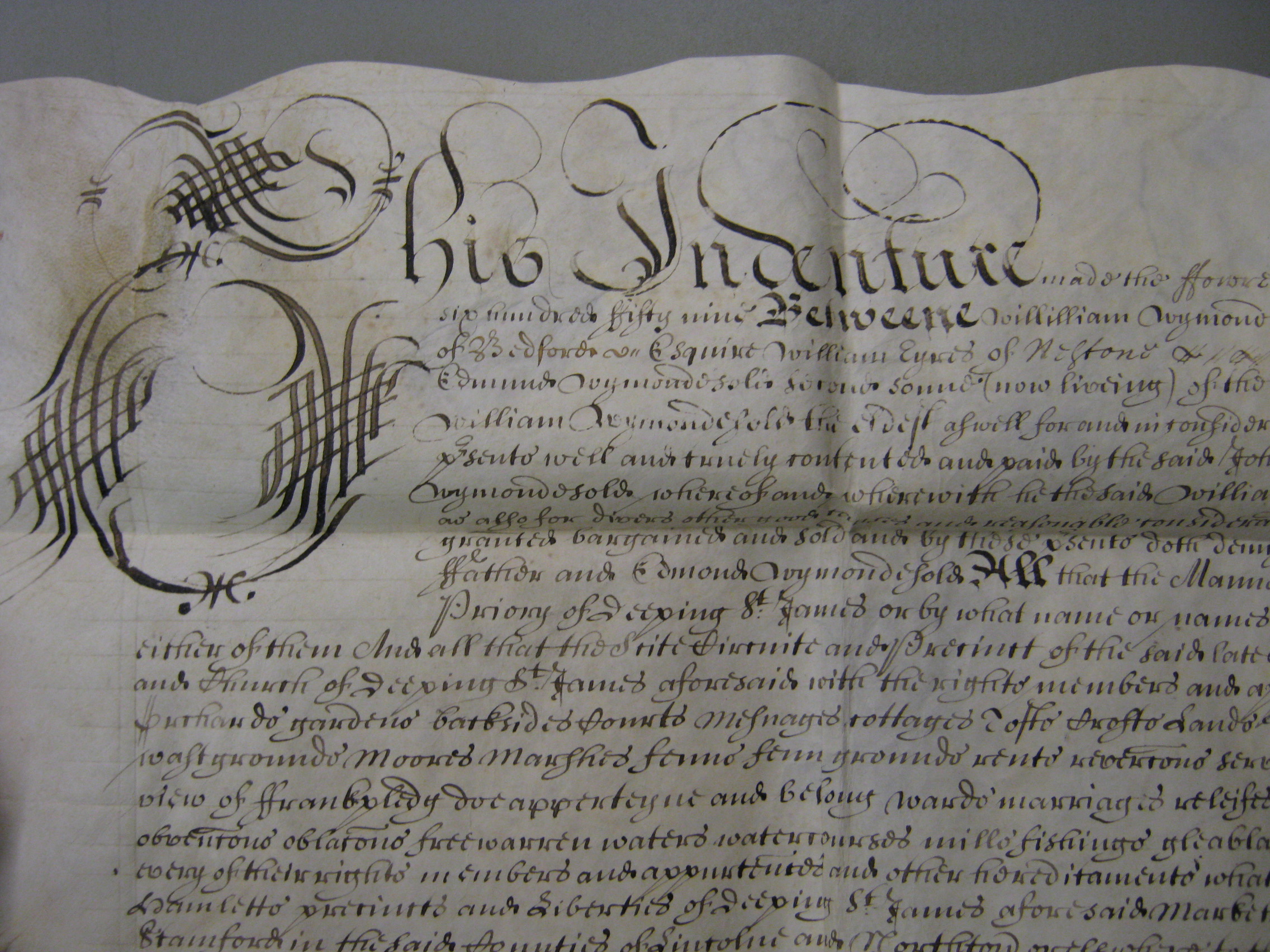

However, by the early 17th century, the manor of Deeping St James was in the hands of the Wymondsold family and it was at this time that a new house, first known as Priory farmhouse, was constructed using original stonework from the demolished 12th century priory buildings. The Wymonsold family, also of Putney (now south west London) and Berkshire, are believed to have been responsible for building the priory farmhouse. Several 17th century deeds confirm the Wymondsold ownership of the manor of Deeping St James, ‘late called the cell of Thorney otherwise called the late priory of Deeping St James’, which included the priory farmhouse.

William Wymondsold was High Sheriff of Putney at a pivotal moment in history, during the Civil War, and at the time of the Putney Debates, held at St Mary’s Church in Putney in 1647. The Debates were held between members of Oliver Cromwell’s New Model Army, including Oliver Cromwell, Henry Ireton, and Sir Thomas Fairfax, and other politicians and soldiers to discuss the future of England and pivotal constitutional questions, including the rights of men and freedom of speech. At this time, it has been recorded that the Parliamentary Commander Sir Thomas Fairfax, was billeted at the home of William Wymondsold (the largest house in Putney – formerly located on the site of Putney train station).

After the Restoration of the Monarchy, several members of the Wymondsold family were noted Royalists and were favoured by a succession of monarchs. Charles II was said to have favoured Sir Dawes Wymondsold, and during the 1660s and 1670s William Wymondsold was recorded as a ‘Royal Ayd unto the King’ (‘Ayd’ being in the form of finance), and in 1684, King James II knighted Robert Wymondsold.

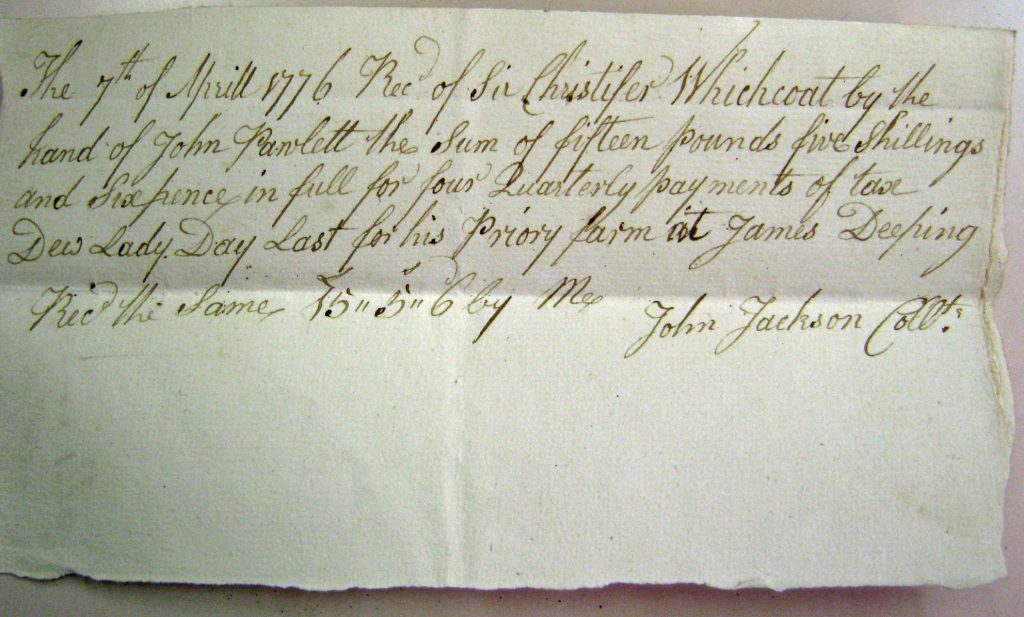

Meanwhile, life was continuing at the Priory Farmhouse in Deeping St James. By the early 18th century, the manor of Deeping St James had passed to the Whichcote family. They were a prominent local family, who were later based in Aswarby Hall near Sleaford (now demolished). By 1776, the manor was held by Sir Christopher Whichcote, and a surviving rent receipt reveals the occupant of the priory farmhouse was Mr John Pawlett.

Rent books and further records reveal John Pawlett was living at Priory Farmhouse, while farming over 400 acres of surrounding land. John Pawlett was also actively involved in the local community and was recorded as an acting vestryman (early council member) and was an overseer of the poor, responsible for distributing poor relief to those in need within the parish. John’s son, also named John, followed his father at Priory Farmhouse, and also in his involvement in community affairs and later, during the 1840s, he became chief constable of Deeping St James.

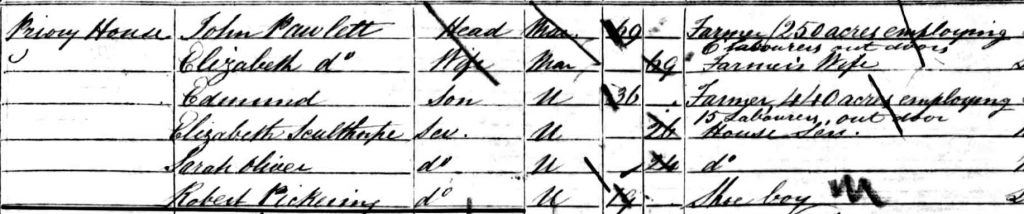

The Pawlett family continued at the Priory Farmhouse throughout the 19th century, when it was recorded with several names, including ‘Priory House’ and ‘The Priory’. The 1851 census reveals John Pawlett, junior, with his wife Elizabeth, living at ‘Priory House’ and John was farming ‘250 acres and employing 6 labourers outdoors’ and in addition, their son, Edmund, was also farming ‘400 acres and employing 15 labourers outdoors’. The family also had three live-in servants.

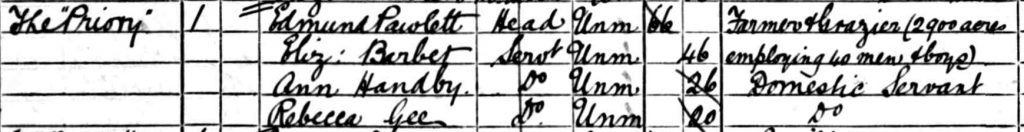

Edmund Pawlett followed his father at Priory House and by the time of the 1871 census he was farming 800 acres and employing 20 men and seven boys. Edmund Pawlett did not marry and the 1881 census shows he was still living at ‘The Priory’, 66 years old, and by this time he was farming and enormous area of ‘2900 acres and employing 40 men and boys’.

Like his father and grandfather before him, Edmund Pawlett played a key role in the life of the local community and, along with providing employment for many local men, he was involved in the formation of the school board in 1876, on which he continued to serve into the 1880s. Edmund passed away in 1885 and for the first time in over 100 years the house became the home of a different family and it passed to farmer, Richard Ward.

Richard Ward and his son, Albert, continued to farm at ‘The Priory’ through to the early 20th century, but by the 1920s the impact of the First World War, along with changes in the ownership of the farm and house, brought about several changes. By the 1950s it had passed through several owners and, in 1959, it was sold again and became the home of Mrs Doris Hall. Mrs Hall continued at the Priory Farmhouse for almost 30 years and in 1987 she sold it to the Rickard family. By this time, the 17th century house was in much need of care and attention. The Rickard family set about restoring and renovating the house and its many historic features.

Now known as St Benedicts Priory, the Grade II* listed house has seen many alterations and changes, but it still retains a number of original features, including a dogleg staircase with turned balusters, as well as an original studded door, and moulded stone mullion windows. It also has a few features that give a glimpse of the former history and the association with the Benedictine priory.